Someone wrote to tell me a solitary poker pic doth not a blog entry make. Well, phooey. How about twelve images from the holidays with captions?

Category Archives: Uncategorized

A Bed Instead

These days, my mother rarely sits in front of the computer. I’ll log-on with iChat and she’ll be lying in bed, napping, watching TV or otherwise playing dead. Late Saturday morning I saw her bright face, up close, clicking away.

“Something funny happened last night,” she said as soon as she realized I was watching her.

“What?”

“Do you remember our friend Fred Howard? Mack tutored him in high school and I gave him your aquarium.”

“No memory at all of him. Go on.”

“He doesn’t have a job and what work he gets pays almost nothing. I don’t know where he lives, but Saturday night he knocks on our door. He’s had a fight with his wife Tiesha, over his cell phone. She thinks he’s sold it. “

“Fill me in a little more. He’s beginning to sound like your friend Ron who added a zero or two to that check he begged Mack to write and then ended up dead.”

“No, Fred’s not a drug addict. He’s a good looking guy, he’s big, over six feet tall, and no fat. He looks like he’s capable of doing hard work. You might hire him, but here he is asking for money or a place to sleep.”

“This young guy – he’s in his twenties now? – looking for a handout at what can be charitably described as a private nursing home? He has no one else to turn to? Or he knows he’ll get a few dollars from you?”

“He said, ‘I need ten dollars for a place to sleep.’ I wanted to give him the money, but Mack wanted to give him a bed. The next thing I know, Mack’s rummaging around in the linen closet for blankets so Fred can sleep on the futon in the living room.”

“This story is too good.”

“But it gets better. The next morning Fred gives me this big hug as he’s about to leave and says, ‘Thank you Mrs. Miller. I tell him, ‘You don’t need to be this homeless person wandering around in the cold rain looking for a place to sleep. You’re better than that.’ He says, ‘I’m never going to be in this position again and he walks out our front door. But standing outside is his wife, Tiesha. She’s screaming at him about how he’s sold their cell phone. I can just see the blinds going up in the neighbors’ houses. They walk away together and then the police arrive.”

“Who called the police?”

“You know I’d never tell your sister this story, or my friend, Phyllis.”

“Who called the police?”

“I don’t know. I guess his wife. Two officers come up to me on the porch and they ask if Henry Howard lives here. You know I’ve never liked the police leaning on me. Anyway, I turned to Mack who doesn’t want any part of this and ask, ‘Is Fred called Henry?’ Of course he can’t hear me. So I tell them no, Henry Howard doesn’t live here, but there was a Fred here. All this time I’m doing everything I can not to laugh. Can you imagine what they’re thinking? Here are these two old white folks and Fred is black of course. I tell them it’s nothing more that a domestic disturbance and they can leave now. “

“And did they?”

“They spoke to each other in some kind of code. And then they left.”

That’s the end of the Fred story, but not the end of the conversation. Helen continues to fill me in on the days events and how happy she is and how much she appreciates her kids. “You know, I really have had a good life. My kids are loving and successful, I have lots of friends – everything Is fine. Except for the relationship. Then she laughs loud enough for Diane to hear her in the other room.

As she talks I watch her intently looking at her computer screen. She then asks, “Is that Ginger on the blog?”

“Not recently,” I answer. “You might have clicked on some old pages. She is in there.”

I log on to her computer using Timbuktu. I look at her screen and what do I see?

The cursor scurrying around flipping solitaire cards.

“HEY! You mean you’ve been talking to me AND playing solitaire at the same time?”

I hear an embarrassed, hand-in-the-cookie-jar giggle and then, “How do you know?”

“What do you mean, how do I know?”

“Oh, you can see my screen. Sometimes you see too much.”

Hotel Burnham

Susan called near dinner time to say she’d made it to Chicago. The pet-friendly hotel had a special cocktail hour for dogs and I guess Wex and Duffy needed to be carried back to their rooms.

Found Photo

Click here

Susan’s Journey

Susan left Sunday morning and called later that evening from The Green Roof Inn in Girard, Pennsylvania, which is an I-90 town mighty close to the Ohio Border. Tonight she hopes to make it to the pet-friendly Burnham in Chicago. And from there, weather permitting, home.

I’m still marveling at this adaptable woman. Leaving the order of Torroemore to move in with us, in all of our near-finished or given-up-on chaos, not to mention our way over-committed social life, without a sign of complaint. Yeah, you say that’s easy given we’re all family, but imagine five weeks of trudging to the dungeon that is our basement to do your laundry, the kitchen drawers that fight back as you attempt to open them, the overly occupied bathroom, not to mention our icy driveway that remained a hazard worse than the slopes of K2 for most of her visit.

I know we’ll miss her, but I don’t think I’ll have to strain to hear that sigh of relief when she walks into her house tomorrow night.

Susan's Journey

Susan left Sunday morning and called later that evening from The Green Roof Inn in Girard, Pennsylvania, which is an I-90 town mighty close to the Ohio Border. Tonight she hopes to make it to the pet-friendly Burnham in Chicago. And from there, weather permitting, home.

I’m still marveling at this adaptable woman. Leaving the order of Torroemore to move in with us, in all of our near-finished or given-up-on chaos, not to mention our way over-committed social life, without a sign of complaint. Yeah, you say that’s easy given we’re all family, but imagine five weeks of trudging to the dungeon that is our basement to do your laundry, the kitchen drawers that fight back as you attempt to open them, the overly occupied bathroom, not to mention our icy driveway that remained a hazard worse than the slopes of K2 for most of her visit.

I know we’ll miss her, but I don’t think I’ll have to strain to hear that sigh of relief when she walks into her house tomorrow night.

December 31

I’ve been waiting for La Rad to post a comment to the Hemingway story, but it doesn’t seem like that’s going to happen, so I’m moving on.

Susan, Larry, Robert, Diane, Katherine, Matt, Emma

As I was driving down Central St, I passed by neighbor, Joy. I waved and then I pulled into my driveway. As I got out of my truck, I turned to see Joy had made a u-turn and pulled in behind me. I walked up to her and said,

“We got your grandsons. Another great Christmas card.†(Her daughter has three blonde boys, each a year or two apart, the oldest must be about ten.)

“I didn’t like Kyle’s smile but..â€

“Come on, Joy, you’re a nitpicker. It wasn’t as perfect as last years and …â€

“A professional took that one.â€

“With the sand dunes and the boardwalk and the beach plums?’

“And that boardwalk has special meaning to Bob (her husband), it’s where he grew up.â€

“I didn’t know that. And how did you like our Christmas card?â€

“Next time I’m going to put a note in mine nagging you for yours.â€

“Believe me, you’ve brought it up so many times, your card already comes with that note.â€

The last time I’d talked to Joy was right after Patti died and we’d both, then, caught up on family matters. At some point, we always talk about the two widows, Mary and Dolly, who used to live between us. I’d walk through both yards to get to Joy and Bob’s.

“I guess you heard about Dolly?†My Two Neighbors and Parting Company

“No, I’ve been meaning to visit her again (In the nursing home behind Emerson Hospital).

“Dolly died. She finally got to go to her daughter’s in Texas, but she lived only three months.â€

“Three months?â€

“She had cancer, but no one knew it. At least she didn’t suffer much.â€

“And, Mary, is she still in the same nursing home?â€

“Mary doesn’t recognize anyone anymore.â€

From “How To Read And Why”

by Harold Bloom

Frank O’Connor, who disliked Hemingway as intensely as he liked Chekhov, remarks in The Lonely Voice that Hemingway’s stories “illustrate a technique in search of a subject,†and therefore become “a minor art.†Let us see. Read the famous sketch called “Hills Like White Elephants,†five pages that are almost all dialogue, between the young man and her lover, while they wait for a train at a station in a provincial Spanish town. They are continuing a disagreement as to the abortion he wishes for her to undergo when they reach Madrid. The story captures the moment of her defeat, and very likely the death of their relationship. And that is all. The dialogue makes clear that the woman is vital and decent, while the man is a sensible emptiness, selfish and unloving. The reader is wholly with her when she responds to his “I’d do anything for you†with “Would you please please please please please please please stop talking.†Seven pleases are a lot, but as repetition they are precise and persuasive in “Hills Like White Elephantsâ€. The story is beautifully prefigured in that simile of a title. Long and white, the hills across the valley of Ebro “look like white elephants†to the woman, not to the man. White elephants, proverbial Siamese royal gifts to courtiers who would be ruined by the expense of their upkeep, become a larger metaphor for unwanted babies, and even more for erotic relationships too spiritually costly when a man is inadequate.

From the book’s preface:

There is no single way to read well, though there is a prime reason why we should read. Information is endlessly available to us; where shall wisdom be found? If you’re fortunate, you encounter a particular teacher who can help, yet finally you’re alone, going on without further meditation. Reading well is one of the great pleasures that solitude can afford you, because it is, at least in my experience, the most healing of pleasures. It returns you to otherness, whether in yourself or in your friends, or in those who may become friends. Imaginative literature is otherness, and as such alleviates loneliness. We read not only because we cannot know enough people, but because friendship is so vulnerable, so likely to diminish or disappear, overcome by space, time, imperfect sympathies, and all the sorrows of familial and passional life.

From "How To Read And Why"

by Harold Bloom

Frank O’Connor, who disliked Hemingway as intensely as he liked Chekhov, remarks in The Lonely Voice that Hemingway’s stories “illustrate a technique in search of a subject,†and therefore become “a minor art.†Let us see. Read the famous sketch called “Hills Like White Elephants,†five pages that are almost all dialogue, between the young man and her lover, while they wait for a train at a station in a provincial Spanish town. They are continuing a disagreement as to the abortion he wishes for her to undergo when they reach Madrid. The story captures the moment of her defeat, and very likely the death of their relationship. And that is all. The dialogue makes clear that the woman is vital and decent, while the man is a sensible emptiness, selfish and unloving. The reader is wholly with her when she responds to his “I’d do anything for you†with “Would you please please please please please please please stop talking.†Seven pleases are a lot, but as repetition they are precise and persuasive in “Hills Like White Elephantsâ€. The story is beautifully prefigured in that simile of a title. Long and white, the hills across the valley of Ebro “look like white elephants†to the woman, not to the man. White elephants, proverbial Siamese royal gifts to courtiers who would be ruined by the expense of their upkeep, become a larger metaphor for unwanted babies, and even more for erotic relationships too spiritually costly when a man is inadequate.

From the book’s preface:

There is no single way to read well, though there is a prime reason why we should read. Information is endlessly available to us; where shall wisdom be found? If you’re fortunate, you encounter a particular teacher who can help, yet finally you’re alone, going on without further meditation. Reading well is one of the great pleasures that solitude can afford you, because it is, at least in my experience, the most healing of pleasures. It returns you to otherness, whether in yourself or in your friends, or in those who may become friends. Imaginative literature is otherness, and as such alleviates loneliness. We read not only because we cannot know enough people, but because friendship is so vulnerable, so likely to diminish or disappear, overcome by space, time, imperfect sympathies, and all the sorrows of familial and passional life.

Hills Like White Elephants

Ernest Hemingway

The hills across the valley of the Ebro were long and white. On this side there was no shade and no trees and the station was between two lines of rails in the sun. Close against the side of the station there was the warm shadow of the building and a curtain, made of strings of bamboo beads, hung across the open door into the bar, to keep out flies. The American and the girl with him sat at a table in the shade, outside the building. It was very hot and the express from Barcelona would come in forty minutes. It stopped at this junction for two minutes and went to Madrid.

‘What should we drink?’ the girl asked. She had taken off her hat and put it on the table.

‘It’s pretty hot,’ the man said.

‘Let’s drink beer.’

‘Dos cervezas,’ the man said into the curtain.

‘Big ones?’ a woman asked from the doorway.

‘Yes. Two big ones.’

The woman brought two glasses of beer and two felt pads. She put the felt pads and the beer glass on the table and looked at the man and the girl. The girl was looking off at the line of hills. They were white in the sun and the country was brown and dry.

‘They look like white elephants,’ she said.

‘I’ve never seen one,’ the man drank his beer.

‘No, you wouldn’t have.’

‘I might have,’ the man said. ‘Just because you say I wouldn’t have doesn’t prove anything.’

The girl looked at the bead curtain. ‘They’ve painted something on it,’ she said. ‘What does it say?’

‘Anis del Toro. It’s a drink.’

‘Could we try it?’

The man called ‘Listen’ through the curtain. The woman came out from the bar.

‘Four reales.’ ‘We want two Anis del Toro.’

‘With water?’

‘Do you want it with water?’

‘I don’t know,’ the girl said. ‘Is it good with water?’

‘It’s all right.’

‘You want them with water?’ asked the woman.

‘Yes, with water.’

‘It tastes like liquorice,’ the girl said and put the glass down.

‘That’s the way with everything.’

‘Yes,’ said the girl. ‘Everything tastes of liquorice. Especially all the things you’ve waited so long for, like absinthe.’

‘Oh, cut it out.’

‘You started it,’ the girl said. ‘I was being amused. I was having a fine time.’

‘Well, let’s try and have a fine time.’

‘All right. I was trying. I said the mountains looked like white elephants. Wasn’t that bright?’

‘That was bright.’

‘I wanted to try this new drink. That’s all we do, isn’t it – look at things and try new drinks?’

‘I guess so.’

The girl looked across at the hills.

‘They’re lovely hills,’ she said. ‘They don’t really look like white elephants. I just meant the colouring of their skin through the trees.’

‘Should we have another drink?’

‘All right.’

The warm wind blew the bead curtain against the table.

‘The beer’s nice and cool,’ the man said.

‘It’s lovely,’ the girl said.

‘It’s really an awfully simple operation, Jig,’ the man said. ‘It’s not really an operation at all.’

The girl looked at the ground the table legs rested on.

‘I know you wouldn’t mind it, Jig. It’s really not anything. It’s just to let the air in.’

The girl did not say anything.

‘I’ll go with you and I’ll stay with you all the time. They just let the air in and then it’s all perfectly natural.’

‘Then what will we do afterwards?’

‘We’ll be fine afterwards. Just like we were before.’

‘What makes you think so?’

‘That’s the only thing that bothers us. It’s the only thing that’s made us unhappy.’

The girl looked at the bead curtain, put her hand out and took hold of two of the strings of beads.

‘And you think then we’ll be all right and be happy.’

‘I know we will. Yon don’t have to be afraid. I’ve known lots of people that have done it.’

‘So have I,’ said the girl. ‘And afterwards they were all so happy.’

‘Well,’ the man said, ‘if you don’t want to you don’t have to. I wouldn’t have you do it if you didn’t want to. But I know it’s perfectly simple.’

‘And you really want to?’

‘I think it’s the best thing to do. But I don’t want you to do it if you don’t really want to.’

‘And if I do it you’ll be happy and things will be like they were and you’ll love me?’

‘I love you now. You know I love you.’

‘I know. But if I do it, then it will be nice again if I say things are like white elephants, and you’ll like it?’

‘I’ll love it. I love it now but I just can’t think about it. You know how I get when I worry.’

‘If I do it you won’t ever worry?’

‘I won’t worry about that because it’s perfectly simple.’

‘Then I’ll do it. Because I don’t care about me.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I don’t care about me.’

‘Well, I care about you.’

‘Oh, yes. But I don’t care about me. And I’ll do it and then everything will be fine.’

‘I don’t want you to do it if you feel that way.’

The girl stood up and walked to the end of the station. Across, on the other side, were fields of grain and trees along the banks of the Ebro. Far away, beyond the river, were mountains. The shadow of a cloud moved across the field of grain and she saw the river through the trees.

‘And we could have all this,’ she said. ‘And we could have everything and every day we make it more impossible.’

‘What did you say?’

‘I said we could have everything.’

‘No, we can’t.’

‘We can have the whole world.’

‘No, we can’t.’

‘We can go everywhere.’

‘No, we can’t. It isn’t ours any more.’

‘It’s ours.’

‘No, it isn’t. And once they take it away, you never get it back.’

‘But they haven’t taken it away.’

‘We’ll wait and see.’

‘Come on back in the shade,’ he said. ‘You mustn’t feel that way.’

‘I don’t feel any way,’ the girl said. ‘I just know things.’

‘I don’t want you to do anything that you don’t want to do -‘

‘Nor that isn’t good for me,’ she said. ‘I know. Could we have another beer?’

‘All right. But you’ve got to realize – ‘

‘I realize,’ the girl said. ‘Can’t we maybe stop talking?’

They sat down at the table and the girl looked across at the hills on the dry side of the valley and the man looked at her and at the table.

‘You’ve got to realize,’ he said, ‘ that I don’t want you to do it if you don’t want to. I’m perfectly willing to go through with it if it means anything to you.’

‘Doesn’t it mean anything to you? We could get along.’

‘Of course it does. But I don’t want anybody but you. I don’t want anyone else. And I know it’s perfectly simple.’

‘Yes, you know it’s perfectly simple.’

‘It’s all right for you to say that, but I do know it.’

‘Would you do something for me now?’

‘I’d do anything for you.’

‘Would you please please please please please please please stop talking?’

He did not say anything but looked at the bags against the wall of the station. There were labels on them from all the hotels where they had spent nights.

‘But I don’t want you to,’ he said, ‘I don’t care anything about it.’

‘I’ll scream,’ the girl siad.

The woman came out through the curtains with two glasses of beer and put them down on the damp felt pads. ‘The train comes in five minutes,’ she said.

‘What did she say?’ asked the girl.

‘That the train is coming in five minutes.’

The girl smiled brightly at the woman, to thank her.

‘I’d better take the bags over to the other side of the station,’ the man said. She smiled at him.

‘All right. Then come back and we’ll finish the beer.’

He picked up the two heavy bags and carried them around the station to the other tracks. He looked up the tracks but could not see the train. Coming back, he walked through the bar-room, where people waiting for the train were drinking. He drank an Anis at the bar and looked at the people. They were all waiting reasonably for the train. He went out through the bead curtain. She was sitting at the table and smiled at him.

‘Do you feel better?’ he asked.

‘I feel fine,’ she said. ‘There’s nothing wrong with me. I feel fine.’

Christmas Givings

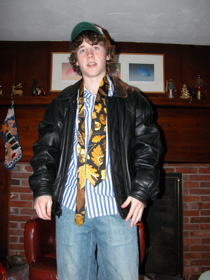

Matt sporting his new leather jacket and one of about fifty Italian silk ties his Aunt Joan sent him.

Suspicious Food

Following up on the last entry:

From the University of Kentucky Department of Entomology

The Japanese have used insects as human food since ancient times. The practice probably started in the Japanese Alps, where many aquatic insects are captured and eaten. Thousands of years ago, this region had a large human population but a shortage of animal protein. Since the area had an abundance of aquatic insects, this food source became very important for human survival. The Japanese still use insects in many recipes. If you were to go to a restaurant in Tokyo, you might have the opportunity to sample some of these insect-based dishes:

hachi-no-ko – boiled wasp larvae

wasp larvae

zaza-mushi – aquatic insect larvae

inago – fried rice-field grasshoppers

Grasshopper

semi – fried cicada

Cicada

sangi – fried silk moth pupae

Pupae

Most of these insects are caught wild except for silk moth pupae. They are by-products of the silk industry. Silk moths are raised in mass for their ability to produce silk. The larvae, the young silk moths, produce the silk. Once they pupate, they can no longer produce silk and are then used as food.